The numbers in the company’s SEC filing are truly eye-popping. Uber has delivered 1.5 billion trips. People paid $41.5 billion for Uber rides in 2018 alone, up 45 percent from the previous year. Uber took $9.2 billion of that as revenue. The company had 3.9 million drivers in the last quarter of 2018.

And, of course, Uber will raise something like $10 billion from its IPO.

Uber almost doesn’t feel like a business, but rather some essential service that investors believe should exist, so they’ve kept injecting money into it. Something so useful would have to make money at some point, right?

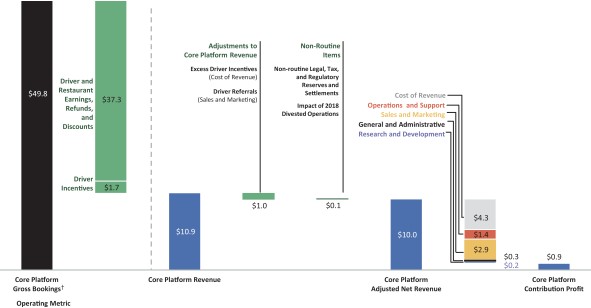

For past and prospective Uber investors, there is some good news. Uber is obviously losing less money per passenger mile than it has in the past. The company is careening dangerously toward profitability, though it’s not there yet. Instead, Uber’s financial team created a different metric that they’re calling “Core Platform Contribution Margin.” This is basically how much money Uber makes on the rides themselves after direct expenses.

Of course, the company has a lot more expenses than the direct ones of providing service. But it certainly seems like an accomplishment to have gotten to bare-bones moneymaking on the core service that the company provides.

That said, Uber’s “Core Platform Contribution Margin” has varied a lot over the last couple years from a high of 18 percent in the first quarter of 2018 back down into negative territory in the last quarter of the year. The company admits that it expects the number to “remain negative in the near term due to, among other factors, competition in ridesharing and planned investments in Uber Eats.”

The company does have another lever, however. Last year, Uber paid out a higher percentage of bookings to drivers than Lyft. As revealed in Lyft’s IPO filing, the company drops 27 percent of each booking into its own pocket. Uber only took 22 percent of the amount a rider pays.

Fundamentally, Uber’s business is still very much like Lyft’s. Huge insurance costs—though declining on a percentage basis—eat a large chunk of revenue. Because there is competition between the two companies, they have to keep aggressively marketing to keep up business. And they have to spend to gain entry to new markets, where other competitors may be entrenched. Uber’s sales and marketing expenses are falling, however, from 41 percent of revenue in 2016 to 28 percent in 2018.

Read: How Lyft’s ride-sharing business works (and doesn’t)

Beyond that, Uber and Lyft differ in some crucial ways. Uber has a remarkably international footprint, with a business or investment in nearly every part of the world. Lyft remains mostly in the United States. Uber Eats and Uber Freight position the company more as an on-demand logistics firm, in which people are only one thing that can be moved. Lyft orients itself more around all types of mobility for people within cities, with major initiatives to build out bike and scooter sharing while partnering with public transportation.

Down the road, autonomous vehicles may become a major part of every ride-hailing business. Uber’s Advanced Technology Group created the first driverless car to kill a pedestrian. Despite that March 2018 tragedy, the company continues to invest in the technology and revealed that they now have 1,000 people working in the Advanced Technologies Group.

My favorite part of any SEC filing is when a company that has never made a dollar castigates itself for this. “We have incurred significant losses since inception, including in the United States and other major markets,” Uber wrote in its filing. “We expect our operating expenses to increase significantly in the foreseeable future, and we may not achieve profitability.”

No matter how its shares fare in the open market, Uber has already changed the world. The company’s model of matching independent contractor labor supply with a pool of demand through an app spawned literally hundreds of imitators. A whole era of internet technology burst forth from the idea of Uber. Uber is no longer a start-up, but its arc is long, and this public debut is merely the end of the beginning.